LTT pathogen testing

The use of LTT in pathogen testing

Since about 2004, the method of pathogen-specific lymphocyte transformation tests has been used in specialised laboratories to assess the current T cell reactivity to pathogens in chronic infections.

The scope of application of the test includes above all obligate or facultative intracellular pathogens, such as Borrelia, Yersinia and Chlamydia trachomatis / pneumoniae, but also yeasts such as Candida albicans. With these pathogens, the symptoms of chronic infection and/or chronic immune activation are almost always unspecific, i.e., the diagnosis is primarily based on lab test results.

However, the LTT is rarely indicated to diagnose fresh infections as in such cases the symptoms and standard lab tests are sufficient (e.g. IgM antibody response, direct detection of the pathogen).

Why is antibody testing alone not enough to diagnose chronic infections caused by certain pathogens?

To detect a past infection caused by the named (primarily intracellularly) persisting pathogens, the pathogen-specific antibodies in the blood are measured (serological diagnosis using ELISA screening tests or immunoblotting). Direct detection of pathogens using microbiological culture techniques or DNA analysis (e.g. PCR) is of little use, at least from blood samples, because these pathogens do not usually persist in the blood, but in tissue. Tissue samples are typically not available for testing, although there are exceptions (e.g. skin biopsies in borreliosis).

- Serology can be false negative

Serological testing (antibody measurements using ELISA or immunoblotting) is not without issues. Specific antibodies only appear 2 to 8 weeks, or even later, after an infection. Depending on the type of pathogen, 5-15% of cases can be expected to remain seronegative (primarily in Lyme borreliosis and yersiniosis). In some cases, the poor quality of serological tests is the cause of seronegativity. In Germany, for example, more than 10 different manufacturers of Borrelia ELISA tests are on the market. No standardisation has been established between these companies. As each manufacturer works with its own target antigens and techniques, serological results frequently differ when tests are performed in different laboratories. - A positive serological result provides no information about the activity of the disease

It is important to understand that a positive serological result does not in any way indicate an active infection requiring treatment. A positive titre (often IgG, at times also IgM) frequently results from a (possibly unnoticed) earlier infection and does not prove a currently active disease associated with the respective pathogenic microorganism. Pathogen-specific antibodies may persist for years even after the infection has cleared, e.g. after antibiotic treatment. In bacterial serologies, this may apply to IgM as well. - Conclusion:

Serological methods can at most provide evidence of past exposure to potentially persisting bacteria. However, no inference can be made as to the present level of activity of the persistent infectious disease. Thus, a pathogen-associated disease can neither be proven nor excluded serologically. In clinical practice, patients all too often undergo, at times prolonged, antibiotic treatment, especially for Borrelia and Yersinia, even though the positive serological result only shows an immune scar. This leads to unnecessary costs. - The LTT can partially fill this gap

It has been shown that this gap in serological diagnostic testing can be largely filled with cellular techniques, such as the LTT. The LTT is only positive when an increased number of pathogen-activated lymphocytes (so-called TH1 effector cells) are circulating in the blood. For bacteria with intracellular persistance, this is only the case when at the time of blood collection the immune system is actively attacks the pathogen. It is known that the number of pathogen-specific T cells in the blood decreases significantly after antibiotic treatment. This is easily recognizable when looking at the falling stimulation index. Most experiences with cellular analyses are related to Borreliosis testing. For this, the scientific literature dates back to the 1980ies (see here). - The validation of the LTT to Borrelia antigens takes several years

The use of the LTT in pathogen testing, especially to detect T cell reactivity to bacterial antigens, is a challenge for every cell culture laboratory. The quality – especially the specificity – of the method depends crucially on the selection of suitable Borrelia antigens. These must contain all protein structures of relevance for the T-cell immune response on the one hand, but on the other hand, no unspecific proteins capable of inducing a positive reaction in non-infected persons must be present. Even though the selection of antigens during preparation phase is difficult (there are few biotechnology companies in Germany dedicated to the expression of this kind of antigens), testing their suitability is actually quite easy.

|

This time-consuming validation of the method was undertaken by the Institut für Medizinische Diagnostik between 2002 and 2005. During this time a cell culture medium was developed to which, besides IFN-alpha, polymyxin B was added to suppress any unspecific activation. The validation studies for the LTT used in the Institut für Medizinische Diagnostik Berlin were submitted for publication to the Open Neurology Journal in 2011 and published in 2012 following a stringent peer review process.

The study shows that the LTT, if correctly performed and suitable test antigens are used, has a sensitivity of 89.4% and a specificity of even 98.7% in sero-negative patients. Especially the demonstrated high specificity invalidates the scepticism towards the method which stems from older studies and is based on the misconception that the LTT generates to many false positive results.

LTT borrelia

Use of the lymphocyte transformation test in clinical testing for chronic borreliosis

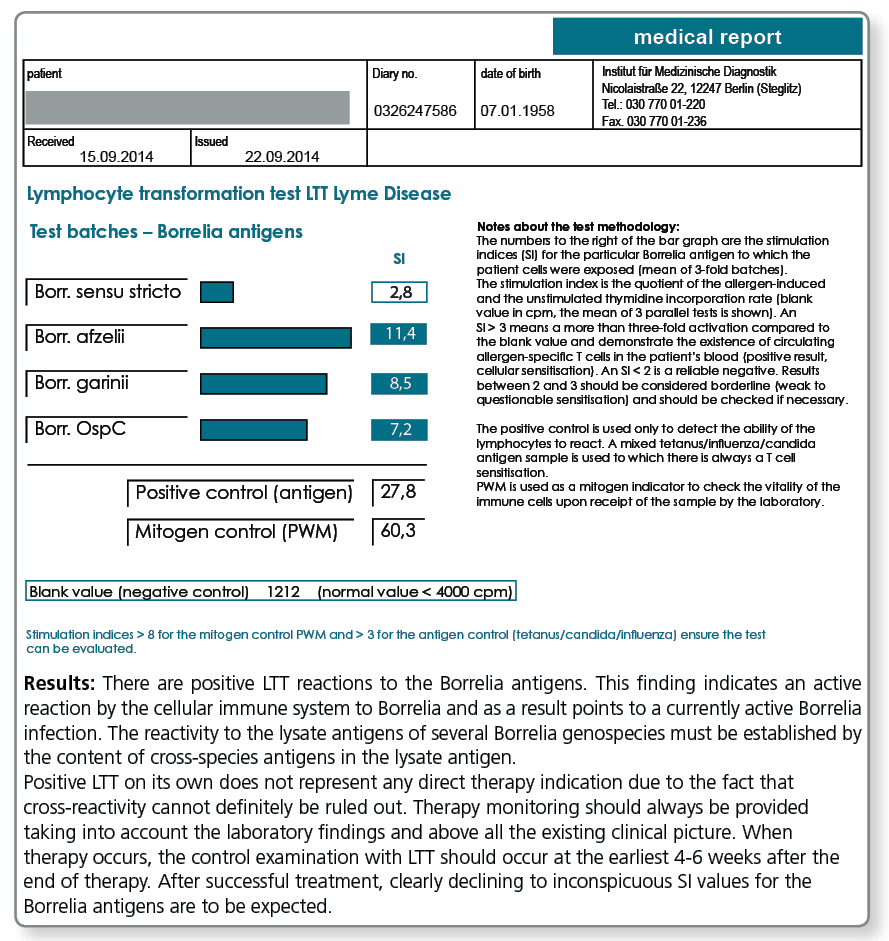

The lymphocyte transformation test with Borrelia antigens detects the cellular immune response mounted by blood lymphocytes against Borrelia proteins. This test is only positive when Borrelia-specific T cells circulate in the patient’s blood. These show that at the time of blood collection the immune system has been involved in an immunological interaction with Borrelia antigens (active borreliosis).

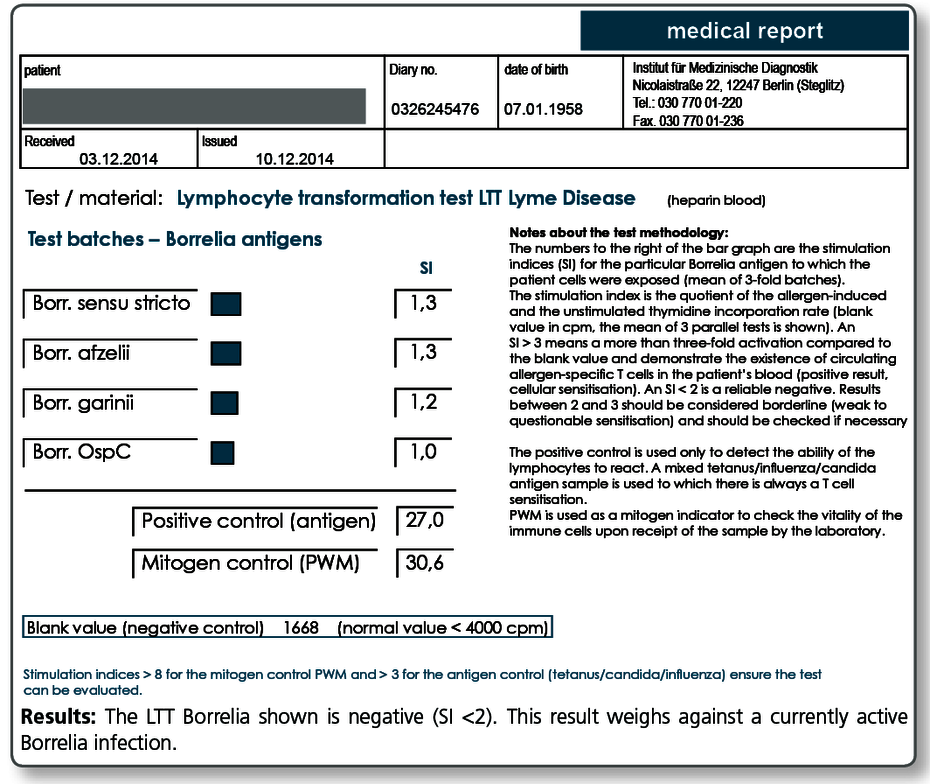

The observation that after effective antibiotic treatment in most cases the LTT becomes negative or at least the intensity of the stimulation indices (SI) considerably decreases, further supports the view that LTT results indeed reflect the activity of the infection. The result of the LTT Borrelia thus informs the treating doctor about the effectiveness of the antibiotic treatment in the respective patient.

A negative result in the LTT-Borrelia, however, does not rule out an active infection with absolute certainty. Therefore, the evaluation of the clinical picture should always come first in the diagnosis of borreliosis and the indication for treatment based on it.

The indications for LTT Borrelia are:

|

Negative LTT results are seen:

- in individuals who never contracted a Borrelia infection

- in clinical healthy, seropositive individuals

- approx. 6-8 weeks after antibiotic treatment of an active borreliosis (baseline results as you can see here)

For more information about the clinical symptoms, diagnostic workup and treatment of Lyme borreliosis see the guidelines of the German Borreliosis Society (DBG) which has been translated into numerous languages. See: www.borreliose-gesellschaft.de/Texte/guidelines.pdf

What sampling material is required?

20 mL fresh heparin blood + 5 mL whole blood (please do not refrigerate)

Literature

- von Baehr V, Doebis C, Volk HD, von Baehr R. The lymphocyte transformation test for borrelia detects active lyme borreliosis and verifies effective antibiotic treatment. Open Neurol J. 2012 ; 6 :104-12.

- von Baehr V. et al. (2001) Improving the in vitro antigen specific T cell proliferation assay: the use of interferon-alpha to elicit antigen specific stimulation and decrease bystander proliferation. J Immunol Methods.;251: 63-71.

- von Baehr R. (2009) Grundlagen zur Lyme Borreliose.umwelt med ges. 22:99-103.

- von Baehr V. (2009) Die Labordiagnostik der Borrelieninfektion.umwelt med ges. 22:119-124.

- Bauer, Y et al.(2001) Prominent T cell response to a selectively in vivo expressed Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein in patients with Lyme disease. Eur.J. Immunol. 31; 767-776.

- Berghoff W. (2009) Klinische Symptomatik der Lyme Borreliose und der Neuroborreliose. umwelt med ges. 22:104-111.

- Breier F et al. (1996) Lymphoproliferative responses to Borrelia burgdorferi in circumscribed scleroderma. Brit J Dermatol.; 134: 285-91.

- Breier F. et al. (1995) Lymphoproliferationstest bei kutanen Manifestationen der Lyme-Borreliose. Wien Med Wschr.; 27: 170-3.

- Buechner SA et al. (1995) Lymphoproliferative responses to Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with erythema migrans, acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans, lymphadenosis benigna cutis, and morphea. Arch Dermatol.; 131: 673-7.

- Deutsche Borreliose-Gesellschaft: Leitlinien zur Diagnostik und Therapie der Lyme-Borreliose. www.borreliose-gesellschaft.de/Texte/leitlinien.pdf..

- Dressler, F. et al. (1992) The T-cell proliferative assay in the diagnosis of Lyme disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 116:603.

- Horst H. (2003) Zeckenborreliose-Lyme Krankheit bei Mensch und Tier.Spitta Verlag 4. Aufl..

- Huppertz HI et al. (1996) Lymphoproliferative responses to Borrelia burgdorferi in the diagnosis of Lyme arthritis in children and adolescents. Eur J Pediatr.; 155: 297-302.

- Kalish RA. et al. (1993): Association of Treatment-Resistant Chronic Lyme Arthritis with HLA-DR4 and Antibody Reactivity to OspA and OspB of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 61:2774-79.

- Krause A et al.(1991) T cell proliferation induced by Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with Lyme borreliosis. Autologous serum required for optimum stimulation. Arthritis Rheum. 34: 393-402.

- Rutkowski S. et al. (1997) Lymphocyte proliferation assay in response to Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with Lyme arthritis:analysis of lymphocyte subsets. Rheumatol Int.; 17: 151-8.

- Satz N. (2010) Klinik der Lyme-Borreliose.Verlag Hans Huber 3. Aufl..

- Schempp C et al. (1993) In vivo und in vitro Nachweis einer Borrelieninfektion bei einer morphe aähnlichen Hautveränderung mit negativer Borrelienserologie. Hautarzt. ; 44: 14-8.

- Steere AC. at al. (1990): Association of chronic Lyme arthritis with HLA-DR4 and HLA-DR2 Alleles. N Engl J Med. 323:219-223.

- Valentine-Thon E. et al. (2007) A novel lymphocyte transformation test (LTT-MELISA) for Lyme borreliosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis.; 57:27-34.

- Wang P. et al. (2001): Contribution of HLA Alleles in the Regulation of Antibody Production in Lyme Disease. Frontiers in Bioscience 6: 10-16.

- Zoschke DC et al. (1991) Lymphoproliferative responses to Borrelia burgdorferi in Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med ; 114: 285-9.

Use of the LTT in other pathogenic bacteria

In other persistent bacterial infections as well, serology reaches its diagnostic limits. The detection of antibodies (positive test result) only shows that at some point in the past the patient contracted such an infection, but provides no information about whether this infection is active at the time of testing. The lymphocyte transformation test detects whether the cellular immune system at the time of testing is still interacting with the pathogen, i.e., whether the infection is active at this point.

The difference in information between the detection of antigen-specific antibodies und T cells is that the T cells detected in the LTT have a limited lifespan compared with antibodies which are likely to persist lifelong.

Therefore, a positive LTT result indicates an interaction of the immune system with the pathogen during the last 4-6 weeks.

| Currently, the LTT is offered for the following pathogens: | |

|---|---|

| LTT Chlamydia trachomatis | LTT Helicobacter pylori |

| LTT Chlamydia pneumoniae | LTT Streptococcus |

| LTT Yersinia | LTT Staphylococcus |

| LTT Giardia lamblia (lamblia) | LTT Candida albicans |

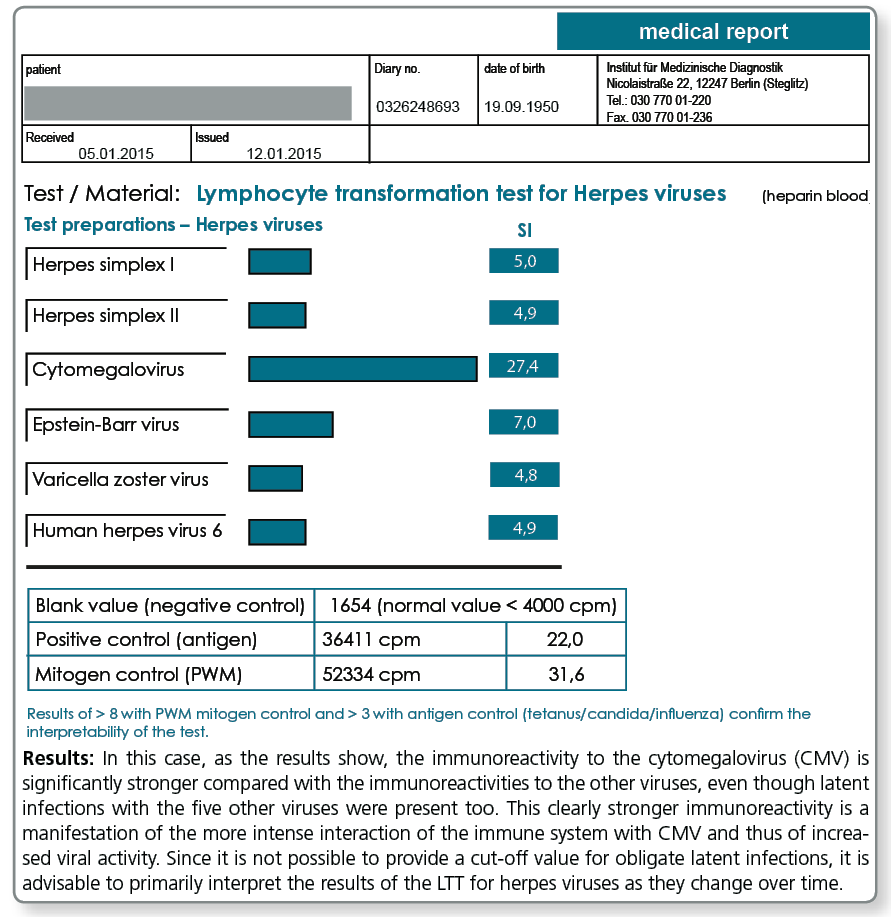

Herpes viruses are special

The pathogen-specific LTT is of particular importance in obligate latent infections (e.g. CMV, EBV or other herpes viruses), because it is almost normal to have experienced an infection with these pathogens at some point in the past and consequently testing for antibodies will always yield positive results. With these obligate persistent pathogens, serology can never differentiate between latent and active infections. When interpreting the “viral“ LTT results, it must be kept in mind that a positive reaction up to a certain level is normal.

The immune system is typically interacting with herpes viruses every day. This distinguishes herpes viruses from Borrelia or other persisting facultative or obligate intracellular bacteria.

The strength of the reaction, however, provides information about the intensity (frequency and duration) of the interaction between the immune system and the pathogen.

A high stimulation index indicates an increased tendency towards reactivation. A noticeably high stimulation index is most significant when the 6 herpes viruses of relevance in humans are considered at the same time, as the differences can then be recognised.

For the following viruses, the LTT can be performed individually or in combination (see profile herpes viruses):

|